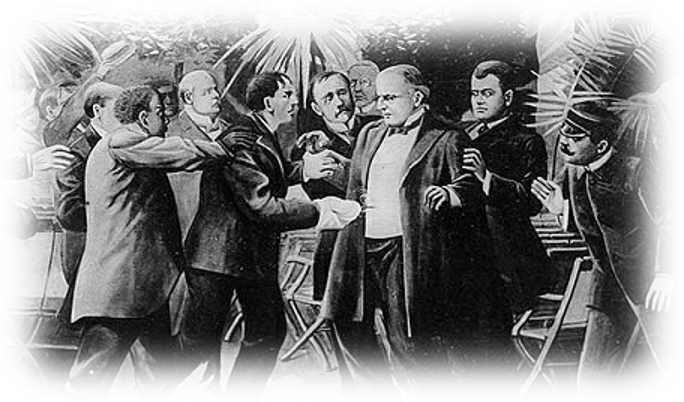

Something feels different about the recent assassinations in Minnesota. While that heinous crime is a tragic feature of even the most stable political cultures, our collective response often reveals far more about where we are “at” than does the violence itself. By my lights, I can think of only two other periods in American history at which time assassinations appeared to become an almost unavoidable fact of political life. The first was at the turn of the twentieth century, when President William McKinley’s murder marked the apex (or nadir) of a string of anarchist-inspired killings of world leaders which had or was to cost the lives of a Spanish prime minister, a French president, an Austro-Hungarian empress, and the kings of Italy, Portugal, and Greece—to name but a few. The second was the late 1960s when, amidst domestic chaos unseen since the Civil War, violence again became a tool for both reactionary and revolutionary forces. Street violence protests the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement culminated (or abyssed) with the 1968 murders of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and New York Senator Robert F. Kennedy—the latter less than five years after a bullet felled his brother in Dallas.

Beyond these two relatively short bursts, assassinations in American life, while always present, long felt more like bugs than features. While politics has become especially, shall we say . . . animated in the last decade or so, I—as I imagine many readers will agree—could not have pictured that two assassination attempts on a once and future president in the span of weeks in Summer 2024 would fade into the background noise with a speed rivalling that of the bullets which had set both stories into motion.

This troubled me at the time . . . but I was not sure why. After all, then-President Gerald Ford’s double brush with death in September of 1975 had also quickly faded into the so-called “dustbin of history,” indeed alongside McKinley’s actual murder. One can choose among several arbitrary distinctions to explain why, say, then-President Ronald Reagan’s 1981 brush captured and retained far greater cultural salience—up there with the mythologized slayings of Presidents Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy. One might assume it is because John Hinckley Jr., unlike Ford’s Squeaky Fromme (a Manson Family nut) or Sarah Jane Moore (her motives remain unclear), actually landed a shot. But what about McKinley? There the man was killed, and certainly his death at the hands of an anarchist with international ties was a greater indictment of its times than Reagan’s “mere” near death on Hinckley’s stated lunatic aim of capturing actress Jodie Foster’s romantic attention.

Another, perhaps more sinister explanation, is that the attempts on Ford’s life came in the immediate aftermath of what he had just described as America’s “long national nightmare”—the preceding decade-plus of political violence, Cold War flashpoints, and the base crookery of President Richard Nixon’s Watergate coverup. In this wake, the attempts on Ford’s life looked like the last dying gasps of a tumultuous era Americans were more than ready to leave behind, while the attempt on Reagan’s just six years later looked more like a one-off once again, and so it had been far easier for us to continue to stomach.

I fear the assassinations in Minnesota—as with the relative public silence on the attempts on Trump’s life—are a harbinger of more violence to come. Sadly, these Minnesota killings already resemble dots on the graph, lost in the mix; and not, as with Reagan’s or JFK’s and Lincoln’s before his, as mere outliers that remain culturally relevant precisely because they were outliers—1963 at the hands of an extremely politically confused diagnosed schizophrenic and 1865 from the gun of Confederate sympathizer who had convinced himself that Honest Abe’s death would reverse the secessionist’s total surrender three days prior.

Granted, each “dot” on today’s graph—hopefully to reach its outer limits in short order—is likely destined for long-term irrelevance no matter what. By all appearances, neither would-be Trump assassin had a coherent political motivation—though the second shooter was apparently angry over what he perceived as Trump’s at best half-hearted support for Ukraine in its ongoing defense against Russia. And, ultimately, Trump survived both incidents. The Minnesota killings, meanwhile, were almost certainly politically motivated—the suspect, since captured, had a list of dozens of officeholders and had visited other politicians’ homes the night of the murders. But few non-presidential assassinations or attempts influence our political discourse even mere months thereafter.

But what if the Minnesota slayings, alongside the Trump attempts, already feel like “dots” instead of outliers because they are mere flareups of a long-simmering politico-cultural illness? What if, as in 1901 or 1968, we already downplay this latest string of political violence as inevitable byproducts of a particularly acrimonious spell? Perhaps the most boorish among us would have tweeted nonchalant, even jokey responses to Lincoln’s and JFK’s assassinations, had there been a social media apparatus through which Confederates and Dixiecrats might have broadcast their shamelessness in realm time—as Senator Mike Lee did last week, in a post blaming “Marxists” above a haunting photo of the masked gunman lurking outside State Rep. Melissa Hortman’s door while he was still armed and on the loose.

My greater fear, however, is that social media not only facilitates the airing of the innermost thoughts some of us have always held, but that it now permits “us”—again, the boors—to announce opinions without fear of warranted social opprobrium. Though the media differ, one especial feature tie 1901, 1968, and 2024-25 together, for worse: We now, as then, live in far larger and more siloed ideological bubbles. Ones in which the loudest, shrieking voices are amplified where in other, more conciliatory periods, the zealous once faced pushback from their own ranks.

Not so today. We are still in the infancy of a new technological age—what philosopher Thomas Kuhn called “paradigm shifts,” in which the newness itself leaves us adrift. Political violence has always intensified as new means of communication dislodge and displace what had started to appear as permanent social mores. Such was the case Western-wide in 1901 (mass printing), in Germany in the 1930s (radio); and 1968 (colorized television). It is no coincidence that civil violence spikes alongside sudden social confusion. Of course it should always be condemned, but so too should it never become accepted, even in resignation.

If we are to end the modern cycle of technology-abetted political violence, we must in real time recognize its provenance. There are always crazies—and thus will there always be some degree of political violence. To which—we should note—there are many practical precautions we have yet to take. Obscuring the home addresses of lawmakers is quite a good start. If you need to talk to them, make an appointment and go to their office. A broader, widespread effort to exorcise and admonish rhetorical allusions to political violence couldn’t hurt, either. Indeed, history shows that as our latest communications shift matures, time-tested social norms will reemerge, reducing temperatures that today so enflame a small subset to act on popularized fantasies of finding violent solutions to discursive problems.

To do this sooner rather than later—instead of waiting what might be another decade of normalized political violence—we must all ask ourselves two questions each and every time we engage in political discourse: (1) Am I presenting a political disagreement as inherently intractable? (2) Am I intimating that my political opponents are perfidious and not just stupid? Self-censoring our most outlandish rhetoric is a hallmark of political civility. It makes us a healthier society. It also provides far less mental ammunition to unstable characters who mistake what most of us recognize as rhetorical hyperbole for a genuine desire—even a rousing demand—for the bullet before the ballet.

We are in a quite dangerous place. And politicians are justified in their fears—as are the countless would-be candidates who avoid public service to save their lives. Americans will adapt to today’s sui generis communications technology. But many more might be hurt, or even killed, if we—the mass of normies—continue lighting rhetorical fires for shits and giggles.

Alki,

Sam Spiegelman