The idea of celebrating America’s independence by blowing up a “small part of it”—as The Simpsons once put it— is as old as the nation itself. Independence Day with fireworks came straight from the Founding Fathers. On July 3, 1776, with the Declaration’s ink still drying (yes it was physically signed on the 3rd), John Adams predicted in a letter to his wife, Abigail, that the date “will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival” to be heralded with“bonfires and illuminations from one end of this Continent to the other.” Adams was, by then, well-versed in the American aptitude for, shall we say . . . exuberance. In 1773 he faced down sneers and jeers—and countless threats of violence—for representing the British soldiers who fired on a civilian protest in Boston. Among the Founding Fathers, Adams, in particular, knew Americans needed a show—a “spectacle,” as detractors might say. Granted the early celebrations were far more explosive than modern-day Independence Day displays—though latter-day events are no stranger to injury.

Early Fourth of July events included public readings of the Declaration, cannon fire, musket volleys, bonfires, and yes, fireworks. Congress made July 4th an official federal holiday in 1870. By the nation’s centennial in 1876, fireworks had become a centerpiece of the day’s festivities. There are few records to piece together the extent of injuries sustained during the first century-plus of celebrations, but advances in record-keeping by the start of the twentieth century paint a fairly bloody picture.

In 1903 alone, records show 4,499 fireworks-related injuries and hundreds of deaths from Independence Day fireworks displays. The century’s first decade saw some 1,500 Americans die in such incidents. Injuries ran the gamut from lost fingers and blinded eyes to severe burns and tetanus infections—termed “patriotic lockjaw” in contemporary tabloids. America’s national birthday had, in short, became a notably deadly affair. Progressive activists (read: party-poopers) soon launched a “Safe and Sane Fourth of July” movement intent on using the heavy hand of the law to keep the actual hands of the American people intact.

For a while it . . . sort of worked. Many municipalities replaced free-for-all fireworks with professionally managed displays, concerts, and other controlled festivities. In an era otherwise famous for laissez-faire attitudes, fireworks became one of the first consumer hazards to spur a nationwide regulatory response. The public largely came to accept that blowing one’s hand off was neither a necessary nor desirable form of patriotism and by 1912 annual fireworks-related fatalities had fallen to as low as twenty, averaged out. And while the nation was decades away from widespread consumer regulation, the safe-and-saners demonstrated a path forward. Though it would not be long before market forces brought some good-ol’-American grisliness back to the day.

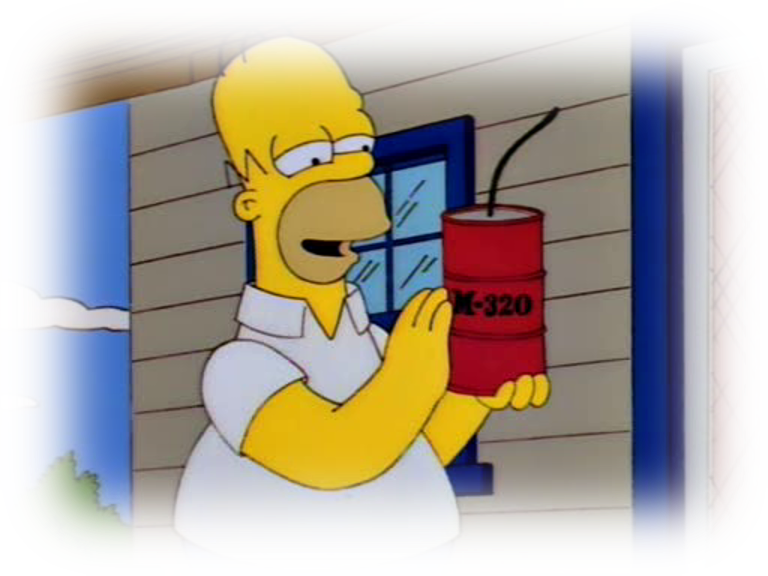

By the 1950s and 1960s, Americans could purchase powerful firecrackers and rockets from roadside stands or mail-order catalogs. New devices—M-80s, cherry bombs, and silver salutes, packed truly alarming firepower—packing almost dynamite-stick firepower. The result? An uptick in fingers lost and new calls for regulation, this time at the federal level. In 1966, Congress banned the sale of M-80s and their ilk. The law also capped the explosive content of all consumer firecrackers at 50 milligrams of flash powder. For perspective, a typical M-80 contained upwards of 3,000 milligrams of flash powder. Buzzkills.

And federal oversight didn’t stop there. In 1974, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (“CPSC”) tried to blanket-ban all consumer firecrackers in 1974, citing continued injuries. Americans, however, would not give in without a fight. Public pushback triggered a compromise. In 1976, the CPSC permitted small firecrackers and fountains, but proscribed any ordnance exceeding “safe” limits—e.g., reloadable aerial shells. Yes, those were once available to ordinary consumers. State and local governments doubled up as well. Even with federal rules culling the worst devices, many states opted to go further. At the peak, nearly half the states had outright banned all consumer fireworks (allowing only permitted public displays). New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Delaware—people’s republics, all—effectively became fireworks no-go-zones, where even a humble sparkler was contraband. Other states chose a middle path, permitting only the milder devices defined as “consumer fireworks” under federal law—products that “don’t go up or blow up” like fountains, sparklers, spinners, and tame firecrackers with limited powder.

By 2001, only nine states still maintained total prohibitions. Most others allowed some mix of consumer fireworks, and a few (especially rural states with prominent fireworks industries) allowed virtually all devices meeting federal limits. This discrepancy gave rise to a new American tradition: fireworks smuggling!! Each summer, freedom-lovers would hop and skip a few miles over their states borders, load up on roadside fireworks, and haul them back home to celebrate their freedom . . . with extreme prejudice. With this one-thousand-blossoms-bloom approach, the late 1990s and early 2000s saw a rise in fireworks-related injuries. In 2000, the CPSC reported approximately 11,000 fireworks injuries necessitating emergency-room visits.

Washington State is not immune to the phenomenon—indeed, it features some of the wackiest fireworks mishaps in recent memory. In 2021, the King County Council outlawed all consumer fireworks in unincorporated areas (where they have direct jurisdiction). Once again, freedom-lovers came to the swift defense of our core liberties, with one fireworks lobbyist calling the ban an offense to the very “principles of America.” Despite local efforts to ban consumer fireworks, Washingtonians still have ample access via Native American Reservations, where regulations track federal standards, not state or local ones. The Evergreen’s summer climate presents risks well beyond the limbal constitution of its most trigger-happy residents.In 2024, fireworks caused at least 270 separate fires across Washington State, per the Department of Natural Resources. These ranged from small brush burns to multi-acre wildland blazes.

Centuries on, fireworks occupy a quirky niche in American life. They are, in one sense, explosives in the hands of amateurs—some, shall we say, of questionable precautionary judgment. But they also symbolize America in its most unvarnished, and raw pride of self—a means of reminding ourselves that we were, from the first—and so happily remain—a rowdy people willing to fight life and limb for each and every iteration of American-style freedom, be it legal, cultural and even—literally—digital. Still, this July 4th, as we don our hockey masks and couch cushions and set our own backyards ablaze, remember that we can always find ways to be free and safe.

Alki,

Sam Spiegelman